by Lilia Leung

Malnutrition takes many forms. Did you know that you can be both overweight and malnourished? While many children today in both developing and developed countries are malnourished and overweight as a result of fast food culture, Africa is still overwhelmingly plagued by malnutrition in the form of stunting, wasting, and being underweight. Stunting (insufficient height for age), wasting (insufficient weight for height), and being underweight (insufficient weight for age) are the main factors of child growth failure (CGF), which is a fundamental impediment to human capital development.

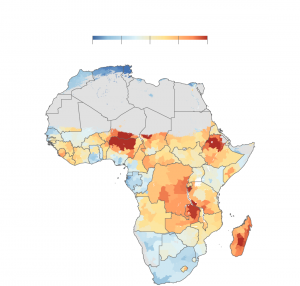

A study published in a recent issue of Nature collected data from 2000 to 2015 and found that while almost all countries in Africa have made overall progress on improving children’s nutrition and health, there are still many disparities between regions, even those within a single country. In particular, researchers found that CGF was notably prevalent in the Sahel region, which is a semi-arid area that includes southern Niger.

Many worldwide humanitarian organizations recognize the need for action on behalf of children in Africa and have set goals aimed at motivating policy change. In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) established the Global Nutrition Targets, which aim to improve nutrition for all children under five by the year 2025. In 2015, the United Nations (UN) adopted the Sustainable Development Goals, which include an objective to end all forms of malnutrition by the year 2030. While the study in Nature projects that all countries in Africa are on course to meet the WHO’s targets for improved nutrition, none of them are expected to reach the UN’s goal to abolish malnutrition completely.

Though some people might consider the goals of the WHO and the UN to be ambitious, both organizations have outlined clear paths toward attainment of these goals. The WHO has come up with a series of five action plans for country officials and policymakers to undertake, most of which include the creation and maintenance of policies, interventions, and programs that support and promote nutrition and healthy eating. Meanwhile, the UN has recommended that countries allocate more funds for social programs and increase investment towards sustainable agriculture and food production.

The issue of malnutrition is, of course, one that is closely tied to water. The most common result of drinking contaminated water is severe diarrhea, which means that even children who have access to sufficient calories and nutrition can become severely malnourished if not provided with clean drinking water. A lack of clean water and hygienic conditions also make children more susceptible to illnesses that result in stunted growth.

The availability of drinking water in many regions of Africa is threatened by the severe droughts, and global warming is exacerbating this already dire situation. Clean water must be prioritized for small children who are the most vulnerable to water-borne diseases. Otherwise, UNICEF warns, as many as 600 million children could face malnutrition, disease, and death by the year 2040.

When we drill a safe water well in a village, child mortality drops by 70% thanks to the combination of clean water, adequate sanitation, and the improved nutrition made possible by vegetable gardens. The answers aren’t complicated; we just need the will to implement them. We can end the world water crisis and child malnutrition in our lifetime.