By Will Beeker

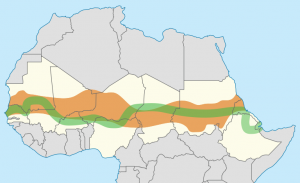

In 2007, a group of African countries in the Sahel region came together with an ambitious plan: planting a 5,000-mile line of trees stretching from Senegal on Africa’s west coast to Djibouti on its east coast to be completed by the year 2030. The aim was stopping the Sahara Desert from creeping southward, a process that has been accelerated by climate change and “denuding” of the land resulting from deforestation and excessive livestock grazing. It was a bold vision that would help preserve the land for future generations.

Source: Sevgart

The project has shown early signs of success. As of 2020, nearly 990,000 acres of land have been restored in Niger alone. Farmers there have begun to see soil health-improving and crops are growing again. Only 18% of the entire project has been completed so far, but much of the last decade and a half has been spent raising funds and planning the massive operation. Plans have had to undergo many revisions as unexpected obstacles have arisen.

Source: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid

As more land becomes usable for crops, less becomes available to pastoralists who raise sheep or cattle as livestock, threatening the livelihoods of millions. Climatologists have also warned that such a sprawling geoengineering project may have unforeseen side effects like worsening monsoon winds as a result of a shift in local temperature and moisture. But the biggest issue was a fundamental one: planting trees is much easier than keeping them alive. As huge numbers of trees died off, the initiative had to adapt.

Source: Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security

Things took a positive turn when the Great Green Wall Initiative started utilizing indigenous land use techniques and breaking down the ambitious program into smaller, more localized projects. For example, farmers in Niger and Burkina Faso discovered new water preservation techniques and started protecting the trees that grew naturally on their land. Farmers in Burkina Faso built zai, grids of deep pits that help to collect and retain water during dry periods. In Niger, farmers started protecting and maintaining the trees that emerged naturally on their farms. These innovative approaches have proven more effective than the one-size-fits-all approach initially conceived when the project began.

These kinds of techniques often originate at a local level, and it can take years for officials to catch up, but once they’re implemented, they can yield impressive results. An ambitious plan like the Great Green Wall Initiative can be a great way to unite different peoples towards a shared goal, but lasting change seems to be most effective when letting ordinary people lead from the bottom up. This is partly because climate change is not an abstract threat for Nigeriens. They feel its effects every day as they farm, fetch drinking water, cook, clean, and even go to school. Their insight into water conservation and land preservation amid arid conditions is invaluable, and Niger’s success in utilizing a bottom-up approach is changing how Africa, and the world, think about sustainability.