By Caroline Moss

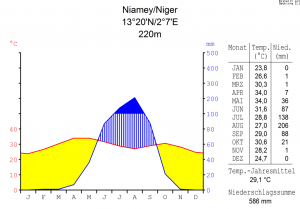

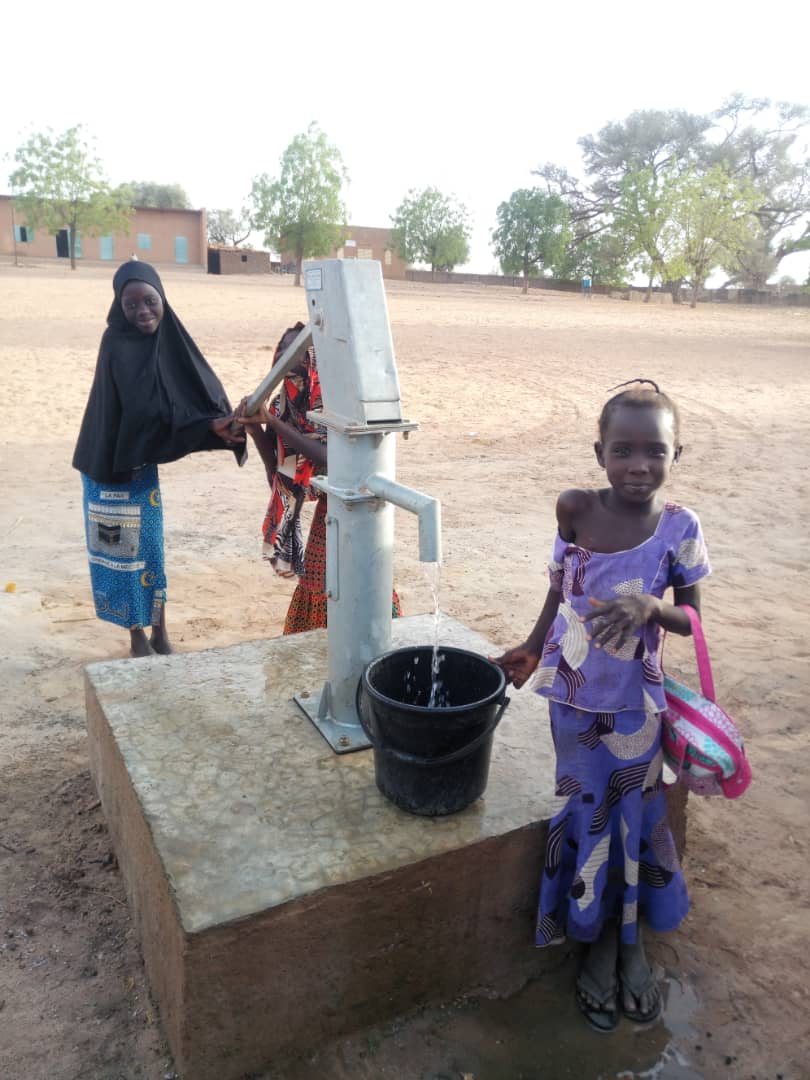

For some, water is available with a quick turn of a faucet, while others have to walk for miles every day to search for and collect water. Access to water is a privilege we often take for granted. Water is an invaluable resource, and easy access to it is a luxury for many people. On average, an American uses about 100 gallons of water per day while average use in sub-Saharan Africa is only two to five gallons of water per day.

- Turn off your faucets.

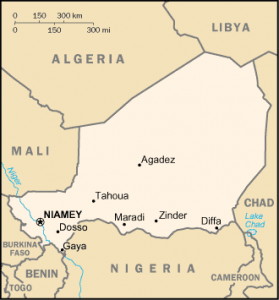

Bathroom faucets run at about 2 gallons of water per minute. What only takes a minute for you will take someone in rural Niger a walk of 3.7 miles per day on average to collect the water necessary for daily life. In your day-to-day, challenge yourself to never leave the faucet running if you’re not using it. Always turn off faucets when shaving or brushing teeth.

- Shorten your showers.

Use your phone timer to hold yourself accountable for shorter showers. Aim for 5-minutes or less. A 4-minute shower uses approximately 20 to 40 gallons of water! An American taking a 5-minute shower uses more water than a rural African uses for all activities in a day.

- Full-loads only!

Only run the washing machine when you have a full load of clothes. Sort clothes by color and challenge yourself to wait to wash until you have a full load. Most high-efficiency washers use 15 to 30 gallons of water to wash clothes. For those in Niger, a washing machine, fishing destination, and drinking water may all be the same place.

- Use the dishwasher.

You might be surprised to learn that pre-rinsing your dishes can actually waste more water than dishwasher itself. If you do pre-rise, make sure to save the water for all of your dishes. A dishwasher uses an estimated 9 to 12 gallons of water per wash. Hand-washing dishes uses an estimated 9 to 20 gallons of water.

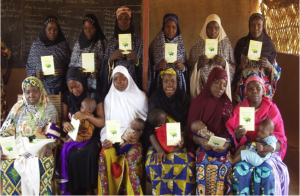

These are just a couple examples of ways to reduce your water consumption. The facts are interesting, but I challenged myself to take the Wells Bring Hope Seven Gallon Challenge to become more aware of my own water usage. The Challenge is to limit our water usage to seven gallons of water per day, which is a high estimate of how much the average rural African uses in a day.

Some parts of the challenge were easy like turning off the faucet to brush my teeth. Other parts of the challenge were difficult. I timed myself for a five-minute shower (3 gallons per minute) and tried to flush the toilet as few times as possible. It made me recognize that my ordinary routine isn’t ordinary and gave meaning to the facts and statistics above. I invite you to take the 7 Gallon Challenge, so that you can experience for yourself how much water the average rural African uses in a day.

SOURCES:

Breyer, Melissa. “36 Eye-Opening Facts about Water.” TreeHugger, Treehugger, 11 Oct. 2018,

https://www.treehugger.com/clean-water/36-eye-opening-facts-about-water.html.

Caruso, Bethany. “Women Still Carry Most of the World’s Water.” Quartz, Quartz, 24 July

2017, https://qz.com/1033799/women-still-carry-most-of-the-worlds-water/.

Cowan, Shannon. “45 Ways to Conserve Water in the Home and Yard.” Eartheasy Guides &

Articles, https://learn.eartheasy.com/guides/45-ways-to-conserve-water-in-the-home-and-yard/.

Houzz. “11 Ways To Save Water At Home.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, 31 Mar. 2015,

https://www.forbes.com/sites/houzz/2015/03/31/11-ways-to-save-water-at-home/#71cc586b166c.

Shryock, Ricci. “Life on the River Niger.” Niger | Al Jazeera, Al Jazeera, 20 Apr. 2016,

https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/inpictures/2016/04/life-river-niger-160414093402652.html.

Watkins, Kevin. “Human Development Report 2006.” Human Development Report 2006, United

Nations Development Program, http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/reports/267/hdr06-complete.pdf.